Our Day (Die Gleichheit, March 29 1911)

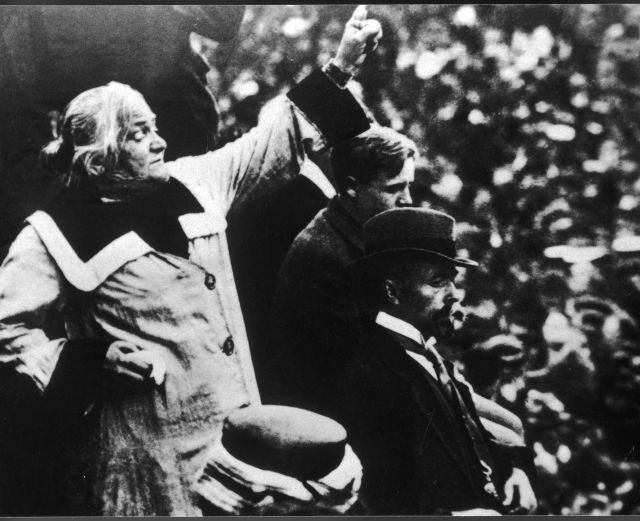

The first attempt to rally the masses of working women internationally around the banner of Social Democracy to fight for the full political and civil rights of the female sex and to present a united, concerted front was a brilliant success. The First Social-Democratic Women’s Day was a great success in Denmark and Switzerland, and especially so in Austria and Germany. This feat should be a lesson to those who have doubts – not about the worthiness or justice of the cause at stake, but about their own ability to lead that cause to victory. In many hundreds of assemblies across national borders, many hundreds of thousands, certainly over a million women and men, were united in expressing their conviction that the female sex deserves the right to vote and to be elected to all legislative and administrative bodies as a recognition of their social autonomy and the social need for them to look after their own interests. And on top of this commitment in principle to equal political, unrestricted rights for men and women, these marching masses were just as united in expressing their will to seize this right from the protectors of age-old injustice in a tenacious struggle. We can note with pride and joy that this International Social Democratic Women’s Day was the most powerful rally for women’s suffrage in the history of the movement for the emancipation of the female sex. Despite its simple outward form, the colourful demonstrations by the English suffragettes, organized with great skill and even greater material resources, pale in comparison to our day and its significance. In terms of their content, the demonstrations by the suffragettes are to the international social democratic rally what a temporarily captivating stage set is to life itself. That is why our demonstration will never be followed, like the huge march of the suffragettes in London, by the farce of a standing a candidate for suffrage, which won a mere 20 votes. The hundreds and thousands who flocked to the various rallies could only take part in these events at the cost of personal sacrifice and inconvenience. And they did so even by sacrificing the first beautiful spring Sunday, which was bestowed upon us in Germany by the capricious weather gods. Those taking part were almost exclusively women and men on whose necks the yoke of merciless capitalist exploitation weighs day in, day out. But precisely for this reason they were driven by a holy resolve of a clearly conscious and well-founded conviction, an unshakeable will to express their views. The struggle for the full political emancipation of the female sex as a right of each individual, free from all privileges of wealth and education, is above all a struggle of working women. It is therefore inseparable from the class-conscious proletariat’s struggle for a thoroughgoing democracy. Its decisive battles will be fought in connection with this struggle, under the leadership of social democracy, by the working and exploited masses without distinction of sex, whose demands for rights are bitterly and stubbornly opposed by the exploiting minority without distinction of sex. In Germany – and, as far as we can tell, in Austria too – this distinctly proletarian-social-democratic character of the struggle for women’s suffrage was expressed in no uncertain terms. In general, bourgeois women were almost completely absent from our rallies, and where they did turn up here and there, they formed a vanishing minority, too weak to make a difference to the character of the events. No surprise here! According to the latest publications, the bourgeois women’s suffrage organizations do not even have 3,000 members. And they are also split between supporters and opponents of universal suffrage. What is more, the feminist [women’s rightist] press did not mention the social-democratic rally at all. This is despite the fact that these very same papers tend to raise a deafening cry of joy if just two people in an American or South African village come out in favour of women’s suffrage. And this is despite the fact that the lively, systematic agitation in the social-democratic and trade-union press and organizations had to make them aware of our event. These facts, however, show more than the weakness, indecision and disunity of the German bourgeois women’s movement in the struggle for the political civil rights of the female sex and the universal suffrage of all adults in particular: they also reveal the politically uninspiring and thick-headed attitude of bourgeois women in general. In this attitude we encounter a sin of bourgeois democracy that mocks it, it does not even know how, in that until recently it fought, and in part still fights against every political awakening of women with the unmitigated narrow-mindedness of the pre-march [March 1848] philistine. The great merit of Social Democracy, which comes to life in the politically alert and mature spirit of hundreds of thousands of proletarian women, differs from this approach like day from night. A mischievous caprice of chance revealingly illustrated the contrast between bourgeois democracy and social democracy on March 19. While the Social Democrats were out demonstrating for women’s suffrage, the central committee meeting of the ‘Progressive People’s Party’ meeting in Berlin raised a toast to ‘the ladies’, as they usually do. No reports indicate that during these deliberations there was any talk of finally listening to the pleas of these fine liberal ‘ladies’ by including the demand for women’s suffrage in that party’s programme. The fact that some bourgeois women’s rightists in Berlin, Nuremberg and Mannheim pledged their sympathy for this move does not alter the decidedly proletarian-social democratic nature of our event. Their solemnly invoked enthusiasm for our struggle acquires a peculiar taste when we recall a few facts. In Berlin, among the bourgeois women’s rightists who welcomed our demonstration for universal suffrage for all adults of both sexes, we found the honest democrat Mrs. [Minna] Cauer and also the ardent fan of the Hohenzollern monarchy, Miss [Maria] Lischnewska. Miss Lischnewska, however, is the founder and leader of the very same ‘Liberal Women’s Party’ that used its hat-pin to stab the proletariat’s struggle for the vote in Prussia in the back by initially declaring itself content with a restricted suffrage. And only last autumn, at the general assembly of the Federation of German Women’s Associations in Heidelberg, did Miss Lischnewska expressly refused to commit this organization programmatically to the demand for the right of women to vote in local elections on the basis of universal suffrage. Mrs. [Elisabeth] Altmann-Gottheiner, however, the intellectual leader of the Mannheim women’s-rightists, sounded the same horn after she had previously avoided taking a position on the burning question of whether we should have suffrage for all women or just for the posh ladies with a cowardly ambiguity. We are not aware of her followers calling her to order for this. But let’s think about the future! It is up to the bourgeois women’s rightists to dispel any doubts about the seriousness and reliability of their convictions. To this end, they only need to back up their words with action. Only when they no longer confine themselves to winning applause at social-democratic meetings by speaking out in favour of universal suffrage, only when they fight for it in the bourgeois world too, as well as in the face of the resistance from it, can they be sure of their status as advocates of democracy. In any case, one thing is certain: the social-democratic rally for universal suffrage for women will help to clarify the situation and have a divisive effect on the movement of the women’s rightists. It is up to the honest bourgeois fighters for equal rights for all to draw the consequences from this, i.e. to oppose with increased vigour and confidence both the open and secret supporters of a ‘moneybags suffrage’ that is passed off as the right of women to vote. March 19 is living proof of the inner unity between the revolutionary class struggle of the proletariat and the striving for the full liberation of the human race. It clearly confirmed that none of the things that oppress the bodies and souls of working women – from the gnawing hunger that is exacerbated by customs and tax usurious policies to their all-consuming longing to develop and exercise their faculties in line with human culture – there is no oppression that the struggling socialist working class does not seriously endeavour to alleviate. It shows that every legal request from the masses of women who struggle with their hands and brains finds an advocate and champion in social democracy. But it also confirms that proletarian women – insofar as they have awakened to class consciousness – give loyalty in exchange for loyalty. Everyone who looks longingly for liberation into the dawn of a new age has gathered around the red banner. In doing so, the female proletarians have shown that they understand the close connection between their individual fate and the historical situation of their class, and recognize that their full humanity can only blossom beyond the prison walls of this capitalist order.

It is from this insight they have drawn the strength to make all the work and struggles of the working class their own. There is not a single activity in the service of proletarian liberation — from the quiet, dusty small tasks of everyday life to the most tremendous struggles for bread and justice—that women do not also feel as their very own cause, and for which they devote themselves to the last fibre of their being. This is recorded in the history of great strikes and lockouts; it is engraved in the tablets of the suffrage struggle and can be observed by anyone who follows the daily shared life of the proletariat, from which its great historical action draws its strength. The social-democratic women have put into their work the highest sum of all the old advantages for which their gender is praised; they are eager to practice all the new civic virtues that the working class needs in order to fulfil its enormous historical task. They, who are often unlearned and untrained, have become knowledgeable, trained and active in strict, voluntary self-discipline with the community. As their tasks have grown, so have they; their work for the shared higher goal has at the same time become work on developing themselves.

From this, they have gained the personal, human advancement and development that the bourgeois social order withholds from them and with which they anticipate an aspect of the liberated humanity of their class. This personal and political maturity was just as indispensable a prerequisite for the brilliant course of the demonstration for women’s suffrage as was the historical insight, the sense of justice, the longing for higher culture on the part of the proletariat’s political and trade-union combat organisations. It is certainly firmly established in history that the decisive victories for the rights of women in bourgeois class society can only be achieved by the armies of the one undivided revolutionary working class. But the other fact that is no less firmly established is that working women themselves must remain the driving force of the fight for this right. For women’s initiative, for the great force of collective action! We owe it to this knowledge that the First International Socialist Women’s Day for female suffrage has become a day of glory for social democracy, a day of glory for proletarian women and socialist women, a political event. It rises up as a landmark that shows us the path on which we advance from stage to stage into the land where socialism, the liberator of humanity, will break the last shackles that society has imposed on women.